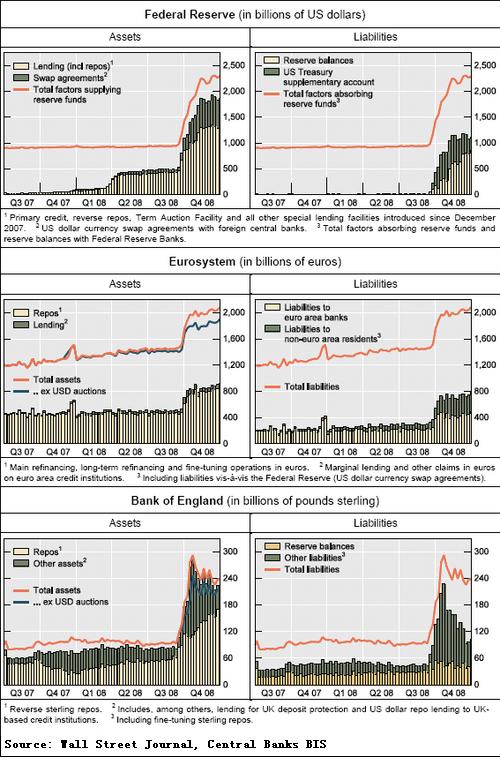

The long wait is over! The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) has just released the results from its Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Market Activity, conducted in April 2010. The report contains a veritable treasure trove of data, perhaps enough to keep analysts busy until the next report is released in 2013. [Chart below courtesy of WSJ].

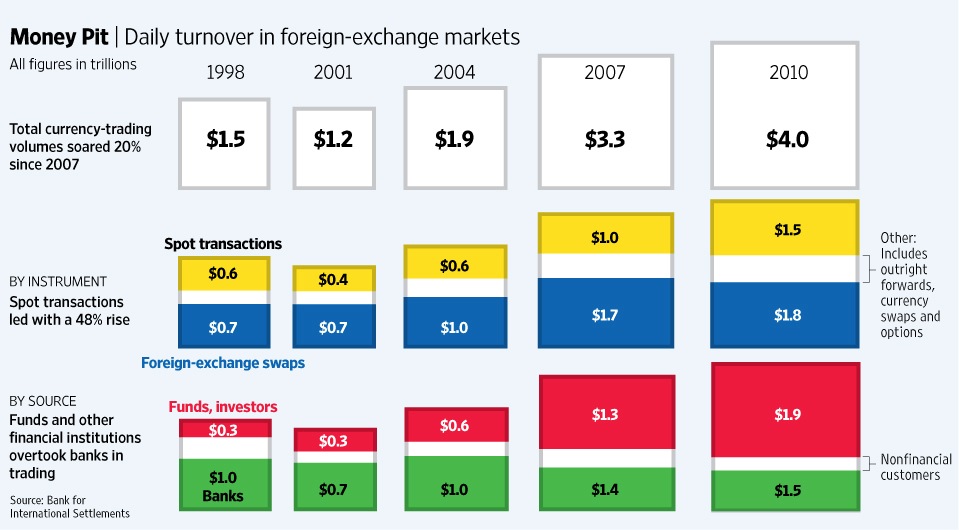

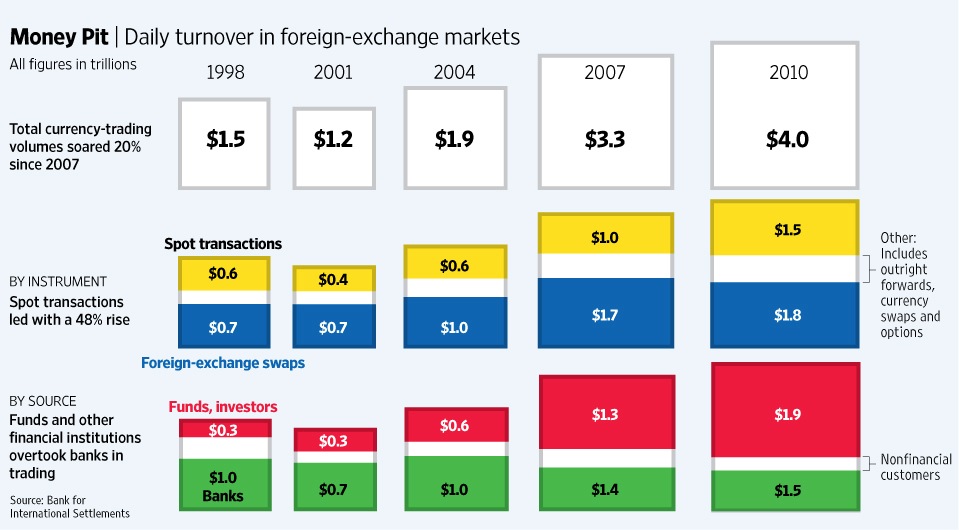

First, the data confirmed earlier reports that average daily forex volume had surged to a record level in 2010: “Global foreign exchange market turnover was 20% higher in April 2010 than in April 2007, with average daily turnover of $4.0 trillion compared to $3.3 trillion. The increase was driven by the 48% growth in turnover of spot transactions, which represent 37% of foreign exchange market turnover. The increase in turnover of other foreign exchange instruments [consisting mainly of swaps and accounting for the majority of forex trading activity] was more modest at 7%.” In addition, for the first time, investors and financial institutions accounted for a larger share of turnover than banks, whose trading activity has remained roughly unchanged since 2004.

First, the data confirmed earlier reports that average daily forex volume had surged to a record level in 2010: “Global foreign exchange market turnover was 20% higher in April 2010 than in April 2007, with average daily turnover of $4.0 trillion compared to $3.3 trillion. The increase was driven by the 48% growth in turnover of spot transactions, which represent 37% of foreign exchange market turnover. The increase in turnover of other foreign exchange instruments [consisting mainly of swaps and accounting for the majority of forex trading activity] was more modest at 7%.” In addition, for the first time, investors and financial institutions accounted for a larger share of turnover than banks, whose trading activity has remained roughly unchanged since 2004.

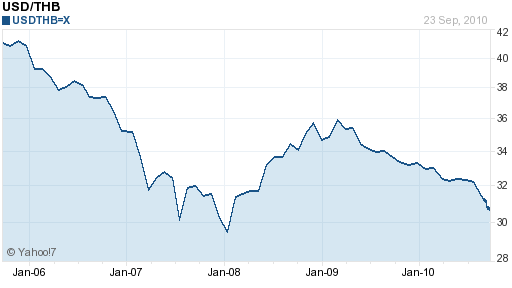

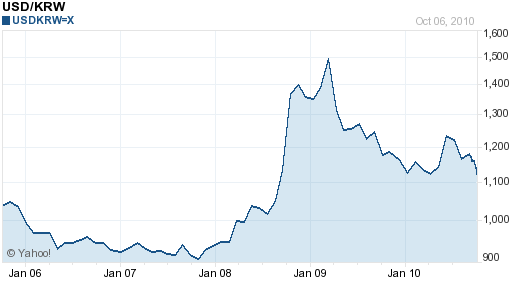

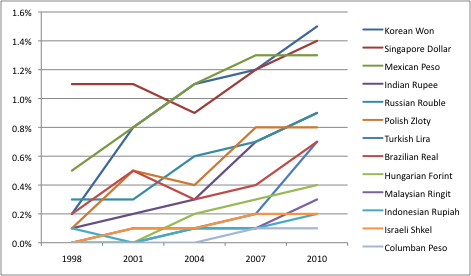

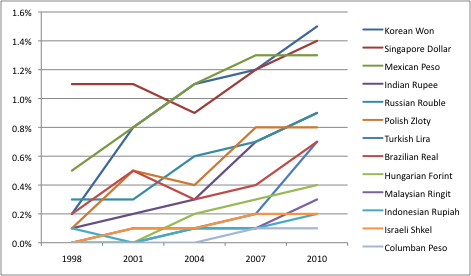

While emerging currencies as a group accounted for a smaller share of overall activity, certain individual currencies managed to increase their respective shares. The Singapore Dollar, Korean Won, New Turkish Lira, and Brazilian Real all fit into this category. Still other currencies, such as the Indonesian Rupiah and Malaysian Ringgit, also managed impressive gains but account for such a small share of volume as to be insignificant when looking at the overall the picture. Those who were expecting even bigger growth should remember that it’s ultimately a numbers game: the amount of Ringgit it outstanding is dwarfed by the number of Dollars, so any gains that the Ringgit can eke out are impressive. In addition, when you consider that the overall forex pie is also increasing, the nominal increase in volume for these small currencies was actually quite large.

While emerging currencies as a group accounted for a smaller share of overall activity, certain individual currencies managed to increase their respective shares. The Singapore Dollar, Korean Won, New Turkish Lira, and Brazilian Real all fit into this category. Still other currencies, such as the Indonesian Rupiah and Malaysian Ringgit, also managed impressive gains but account for such a small share of volume as to be insignificant when looking at the overall the picture. Those who were expecting even bigger growth should remember that it’s ultimately a numbers game: the amount of Ringgit it outstanding is dwarfed by the number of Dollars, so any gains that the Ringgit can eke out are impressive. In addition, when you consider that the overall forex pie is also increasing, the nominal increase in volume for these small currencies was actually quite large.

The ongoing search for yield in all corners of the financial markets is likely to bring some of the more obscure currencies into the fold. “In June, I began getting questions about Uruguay, Vietnam and others,” said Win Thin, senior currency strategist at Brown Brothers Harriman in New York…investors often asked Mr. Thin questions about less-familiar currencies such as the Ukrainian hryvnia and Romanian leu.” In the same article, however, Mr. Thin cautioned that interest in such currencies is still probably lower than in 2007-2008, for a good reason. “It’s not like the Group of 10, or even the more liquid emerging market currencies where, if you decide you’ve made a mistake, you can get out.”Due to the lack of liquidity and higher spreads, these obscure currencies aren’t really suitable for trading. Of course there will be a handful of institutional and even retail investors that want to make long-term bets on these currencies. They tend to be more aware of the risk and less sensitive to the higher cost and lower convenience. The overwhelming majority of traders, however, churn their portfolios daily, if not hundreds of times per day. A 10pip spread on the USD/MXN (Dollar/Mexican Peso) would be considered too high, let alone a 50 pip spread on any transaction involving the Ukrainian hryvnia.

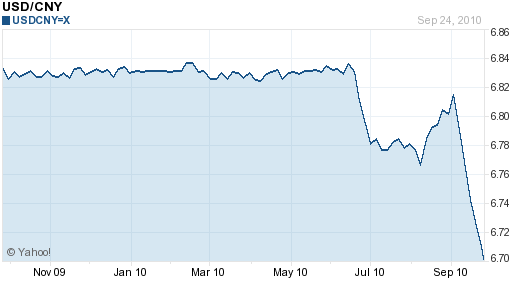

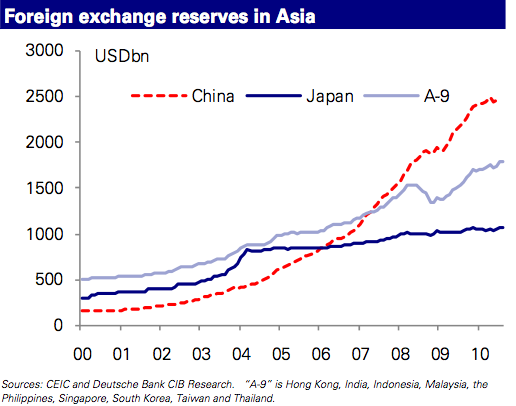

In short, the majors will account for the majority of trading volume for the foreseeable future, regardless of what happens to the Euro. At the same time, that won’t prevent a handful of selected emerging currencies, such as the Chinese Yuan, Indian Rupee, Brazilian Real, and Russian Ruble from increasing their share. As liquidity rises and spreads decline, volume will increase, and their rising importance will become self-fulfilling.

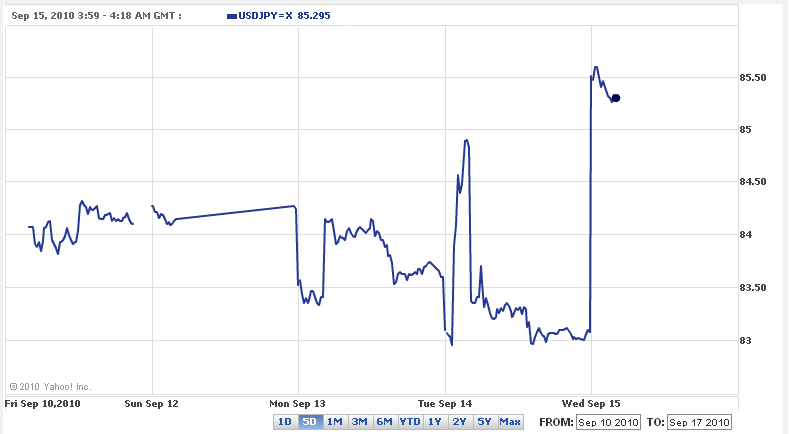

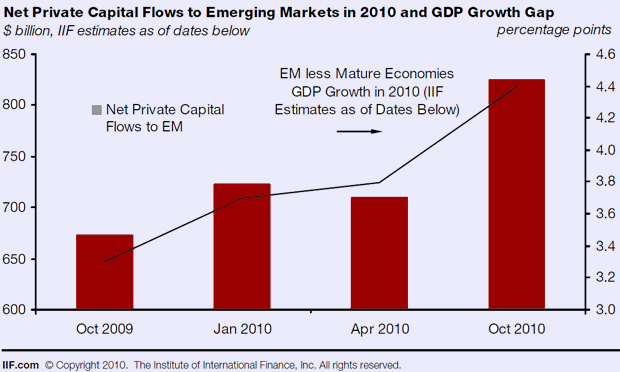

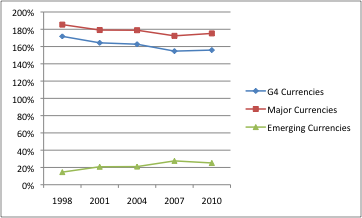

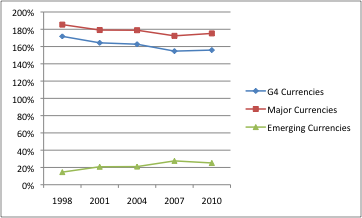

The composition of the turnover actually didn’t change from 2007, interrupting a shift which had been taking place over the previous 10 years. Specifically, the share of overall turnover accounted for by the so-called major currencies actually increased in 2010, from 172% to 175%. [Since there are two currencies in every transaction, total volume sums to 200%]. Growth in the G4 currencies (Dollar, Euro, Pound, Yen) was more modest, however, increasing from 154% to 155%. This reversal is probably attributable to the credit crisis, which drove (and in fact, continues to drive) investors out of emerging market currencies and back into safe haven currencies, namely the Dollar, Yen, and Pound. However, this theory is belied by the significant increase in Euro trading activity, which certainly hasn’t benefited from the recent trend towards risk aversion.

The ongoing search for yield in all corners of the financial markets is likely to bring some of the more obscure currencies into the fold. “In June, I began getting questions about Uruguay, Vietnam and others,” said Win Thin, senior currency strategist at Brown Brothers Harriman in New York…investors often asked Mr. Thin questions about less-familiar currencies such as the Ukrainian hryvnia and Romanian leu.” In the same article, however, Mr. Thin cautioned that interest in such currencies is still probably lower than in 2007-2008, for a good reason. “It’s not like the Group of 10, or even the more liquid emerging market currencies where, if you decide you’ve made a mistake, you can get out.”

In short, the majors will account for the majority of trading volume for the foreseeable future, regardless of what happens to the Euro. At the same time, that won’t prevent a handful of selected emerging currencies, such as the Chinese Yuan, Indian Rupee, Brazilian Real, and Russian Ruble from increasing their share. As liquidity rises and spreads decline, volume will increase, and their rising importance will become self-fulfilling.

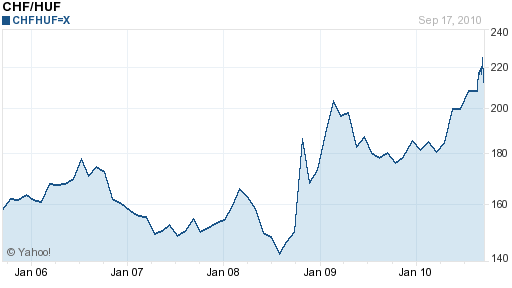

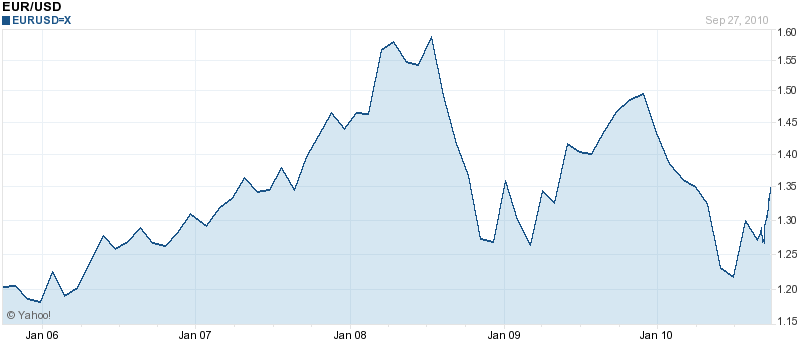

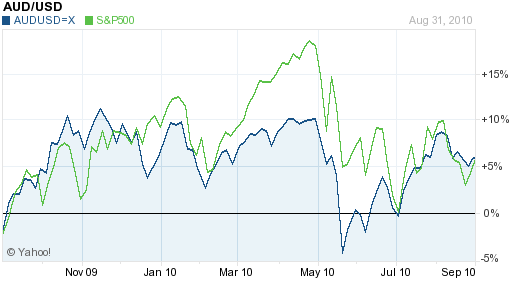

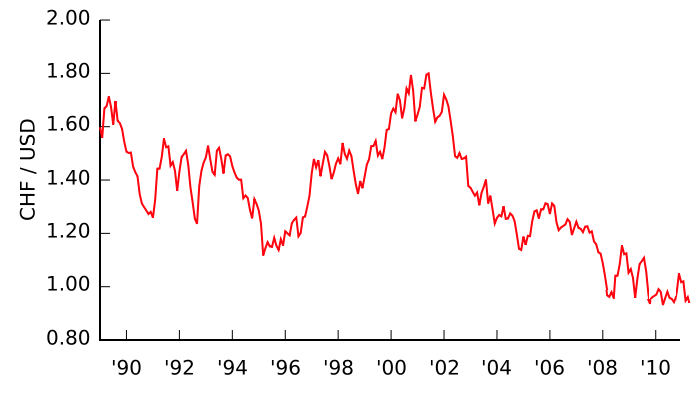

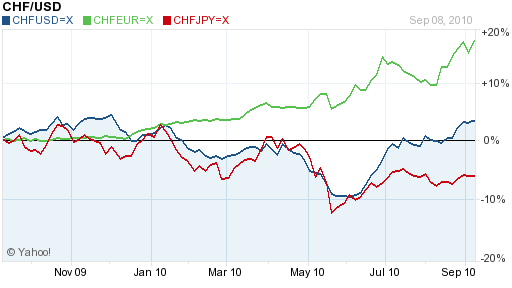

I’m sure serious technical analysts are rolling their eyes at the chart above, but the point stands that trend-following has never been easier and rarely more profitable than it is now. One fund manager summarized, “Trend-following investors are capturing the momentum in several big currency moves. You have so much uncertainty in the world now with regard to inflation or deflation, which typically makes currency markets and interest rates move. That is good for trend followers as it causes volatility, which typically creates good profits.” In other words, there is a tremendous amount happening in forex markets at the moment, and this is reflected in protracted, deep moves in currency pairs, which can change direction without notice and yet continue moving the opposite way for just as long. If you think this sounds obvious, look at historical data (5-10 years) for the majority of currency pairs: while trends have always been abundant, it was only recently that they began to last longer and became more pronounced.

I’m sure serious technical analysts are rolling their eyes at the chart above, but the point stands that trend-following has never been easier and rarely more profitable than it is now. One fund manager summarized, “Trend-following investors are capturing the momentum in several big currency moves. You have so much uncertainty in the world now with regard to inflation or deflation, which typically makes currency markets and interest rates move. That is good for trend followers as it causes volatility, which typically creates good profits.” In other words, there is a tremendous amount happening in forex markets at the moment, and this is reflected in protracted, deep moves in currency pairs, which can change direction without notice and yet continue moving the opposite way for just as long. If you think this sounds obvious, look at historical data (5-10 years) for the majority of currency pairs: while trends have always been abundant, it was only recently that they began to last longer and became more pronounced.